La adquisición de clase media: la música es menos una meritocracia que nunca antes

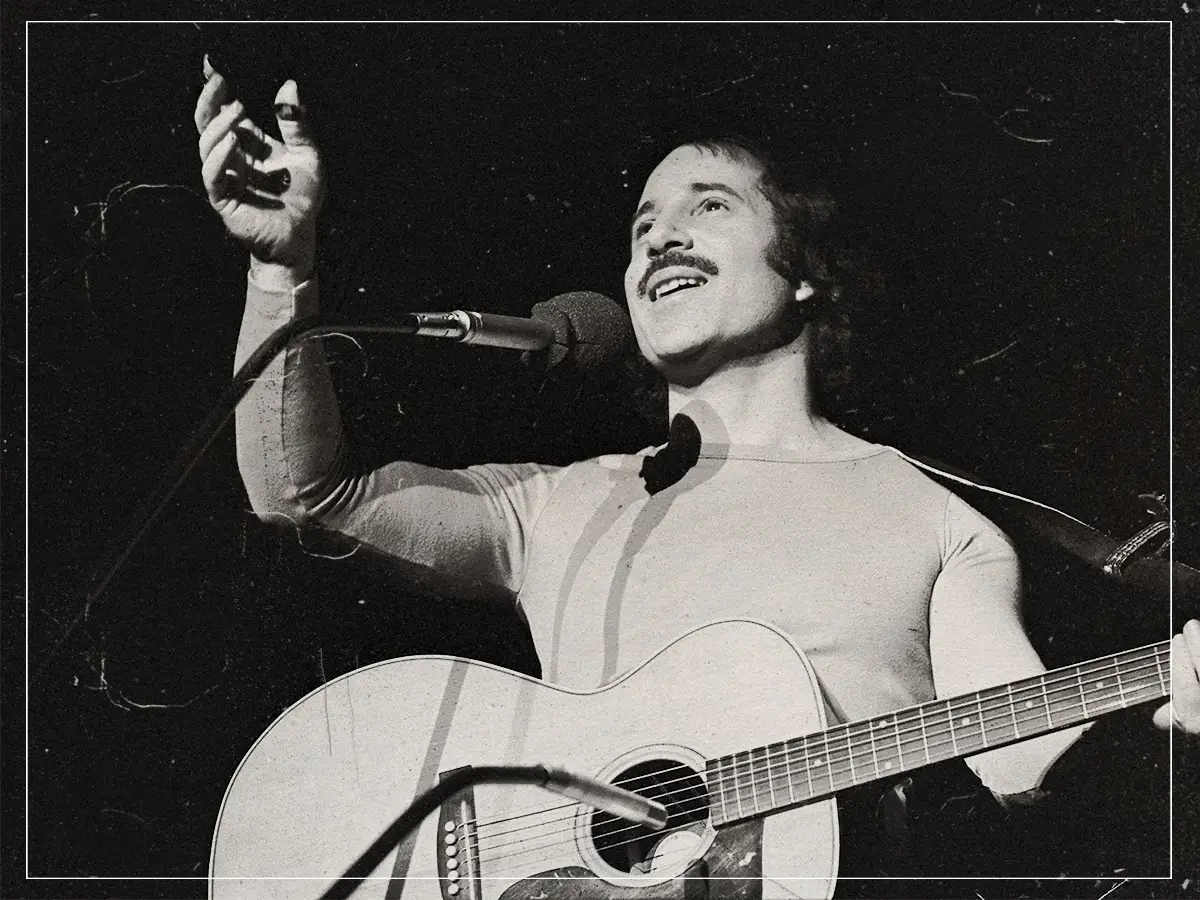

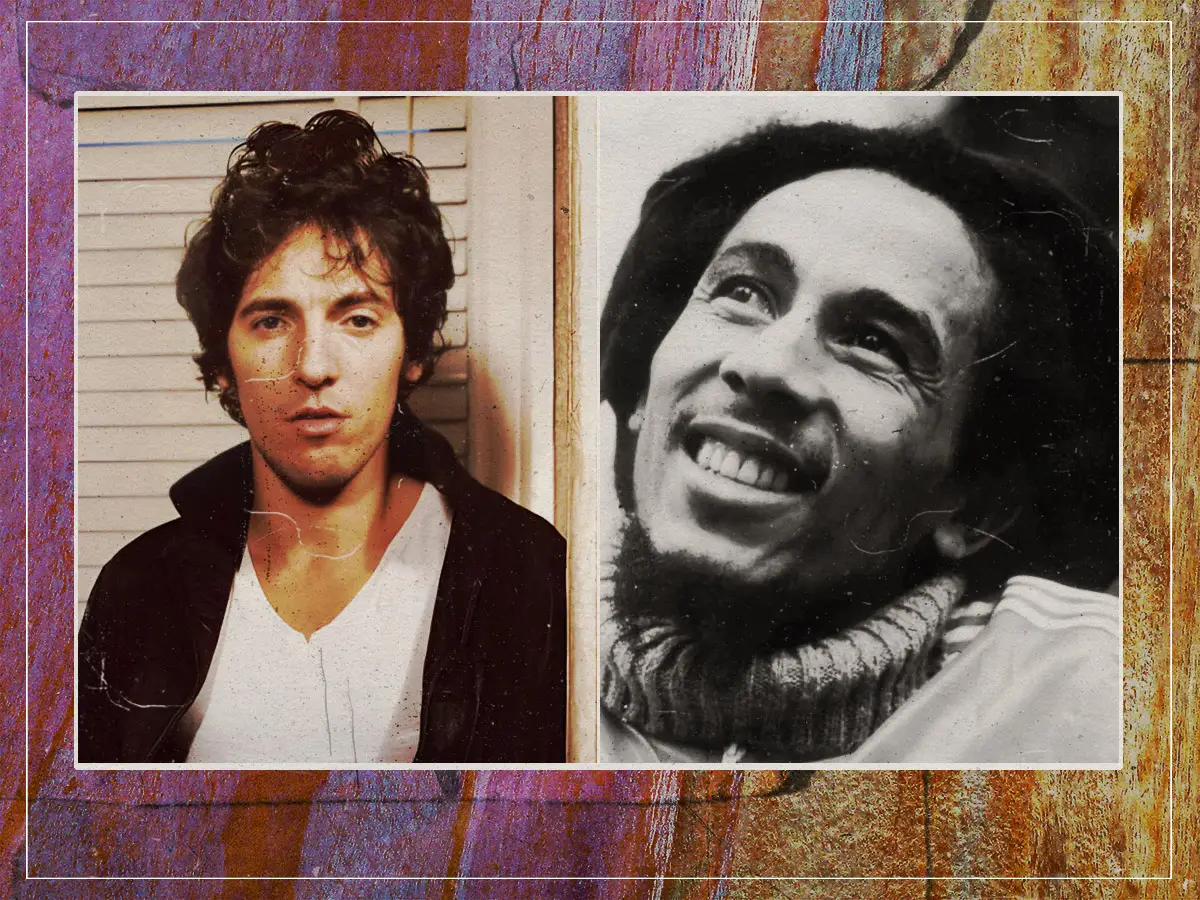

Since the early days of popular music, artists of all backgrounds have contributed to its development. With working-class musicians like The Beatles dominating the industry in the 1960s, music didn’t always seem so glaringly posh. However, these days, working-class artists are finding it increasingly difficult to crack into the industry, with well-educated, highly-connected individuals working their way to the top with considerably more ease.

In the 1990s, Britpop was booming, with artists such as Oasis and Happy Mondays, which featured proudly working-class members, becoming some of the country’s most successful outputs, suggesting that your social background didn’t have to determine your ability to be an accomplished musician. However, as the years have progressed, this seems less and less accurate, with Britain’s music scene rapidly changing shape.

Into the 2000s, it became a reoccurring trend for musicians to pretend to be working-class, hoping to appeal to a broader audience who might view them as relatable, down-to-earth figures. Artists such as Lily Allen and Jamie T seemed like the real deal, boasting cockney accents and singing about Stella-fuelled incidents and the slappers and crack whores of London. Their far-from-polished appearances helped give the illusion that they were from disadvantaged backgrounds and ‘one of the people’. However, Jamie T attended an expensive independent public school in Surrey, and Allen, the daughter of an actor and film producer, was educated at several private schools, including Bedales.

Este fenómeno no ha desaparecido, simplemente se ha vuelto más difícil de detectar. En una entrevista con Aturdido , Big Joanie (an all-female, working-class black band) explained, You pop on the radio, and it’s another white boy band from the north going on about how working-class they are, then it turns out that they went to art school and they live in some posh area of Leeds. It comfortably fits the narrative for what Britain thinks is a good representation of what the working class is, when actually it’s much more diverse than that.

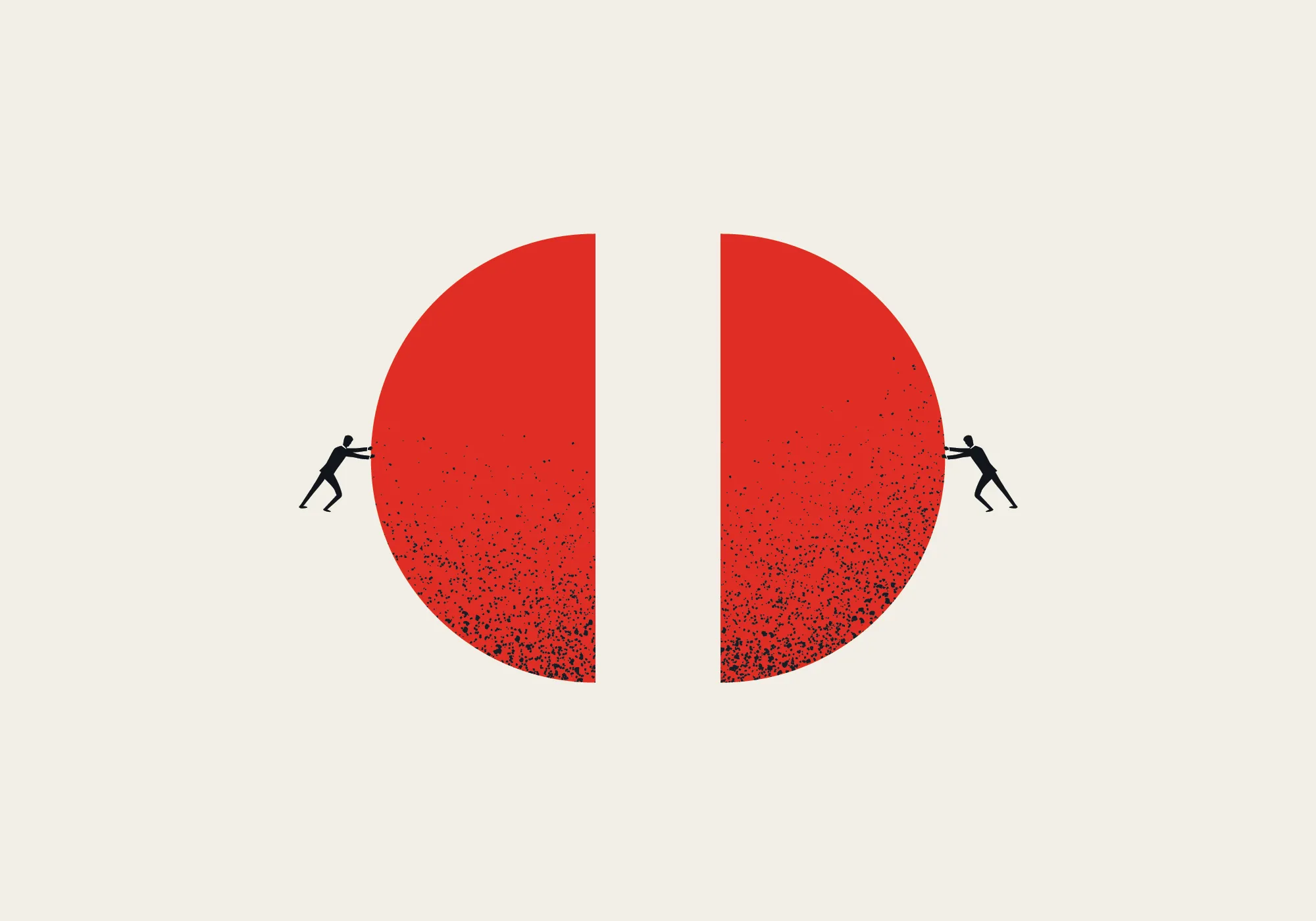

They added, The rock and indie scene is undergoing a middle-classification where less and less working-class musicians can afford to be in bands. For working-class musicians, everything comes out of your own pocket.

The connections, wealth of equipment and opportunities available through private education or being middle-class undoubtedly give musicians a leg up into the industry. Meanwhile, real working-class creatives are disadvantaged for countless reasons, failing to compete against well-off aspiring musicians who don’t have to rely on working a full-time job to pay the bills as they attempt to break into the industry. A recent study published in 2022 discovered that since the 1970s, the number of creative workers (musicians, actors, artists, etc.) from working-class backgrounds has significantly decreased to just 7.9%.

Clearly, a deep-rooted class issue is at the heart of the music industry. Of course, there have been acclaimed working-class musicians, such as Adele, who have risen to prominence in recent years, but the statistics prove that such success stories don’t happen daily. So, why is there such a class disparity in the music industry? When Love Island star Molly-Mae Hague made the tone-deaf comment that we all have the same 24 hours in a day, she epitomised the classist attitudes rife in the creative industry and the myth of meritocracy. Privileged individuals will never understand the common struggle for working-class people to balance work with other needs, such as studying, childcare, rest, socialising and pursuing hobbies. When your main priority tiene Ganarse la vida, canalizar el tiempo y el dinero en un esfuerzo creativo a menudo es una decisión arriesgada en una industria tan cuthroata y discriminatoria.

In turn, privileged people with access to additional music lessons, a wide array of equipment and high-profile connections fill these spaces in the industry, blocking out those born into less fortunate social positions. Of course, many posh, privately educated, nepotistic musicians have made good music; after all, they’ve got few excuses not to. It would be reductive to say that privately-educated people shouldn’t be allowed to make music – then we’d have no Nick Drake or The Strokes or Radiohead. Rather, the music industry, as a mechanism, needs to make internal changes to allow working-class people to find greater opportunities to excel in the musical sector.

Unfortunately, the government are reluctant to finance the creative industries, frequently pulling the plug on funding, gravely affecting lower-class artists. Perhaps this is because the rich fear spreading the voices of the poor; they don’t want to potentially disrupt the social order. Whatever the reasons might be, there are other methods of action that can be taken to allow working-class musicians to attain greater security and opportunities. There’s no reason why established acts with more than enough power shouldn’t use their platform to champion underrepresented artists or fund music institutions in lower-income areas. More events could be set up to showcase talent, provide invaluable resources to budding musicians, and allow creatives to mix with one another and create their own networks.

Music is central to our experience as humans, and no one should be denied the opportunity to create and indulge in it because of the social class they just so happened to be born into. Rather than preventing already-privileged people from joining in, the ladder needs to be made more climbable for those that haven’t been given a headstart.

Sin embargo, con el Costo creciente de giras leading many established acts to have to cancel shows, perform fundraising events, or take a loss of profits, the music industry doesn’t seem to be getting any more accessible these days. Although there certainly are bands emerging from working-class backgrounds that have managed to build up dedicated followings, on the whole, most of the popular acts currently dominating the UK are from middle/upper-class backgrounds.

Hablando con Muy lejos , El cantante de niñas de los EE. UU. Meg Remy resumió perfectamente el estado actual de la industria de la música: en las industrias, el propósito es ganancias. [...] Los músicos realmente están luchando en este momento. Solo están luchando. Mentalmente, monetariamente, creo que en cuanto a la inspiración, en cuanto a la conexión, es un momento nuevo realmente incierto. Si los actos establecidos están luchando, ¿cómo van a romper los aspirantes a artistas desfavorecidos?

A class divide transcends the music industry, it can be found in every sector, and it seems like it’s not going anywhere. All we can do is continue to have these conversations and hope that those with power in the music industry will start making active changes to make it a more inclusive environment. Whether we see that happen anytime soon is another story…

Big Joanie assert, It’s tougher than it’s ever been to be a working-class musician. This is why it’s so important to take a stand: to back campaigns that support bands, join a union, and urge venues to take smaller cuts.